by Mathieu M. Petitjean, Ph.D [1] and Susan Z. Paquette, MBA, MS [2],

The pain points of the U.S. healthcare:

The United States has the largest healthcare services market in the world, representing a significant portion of the U.S. economy. In 2012, the U.S. spent more on healthcare per capita ($8,915) and more on health are as percentage of GDP (17.2%) than any other nation[i]. The related market for medical technologies, including Healthcare IT, represents more than 50% of the worldwide opportunity, turning the U.S. into a very attractive market. Mostly funded by Federal Government programs (such as Medicare, Medicaid, Tricare, CHIP and the Veteran Administration) and employers (though commercial health insurance companies), the economic burden of Healthcare and the daunting forecast to spend 1 dollar of five of the U.S. Economy by 2020 on Healthcare is addressed by multiple private and governmental initiatives to reduce cost and improve effectiveness.

As a result, the U.S. Healthcare ecosystem is now seeking solutions that will (i) Increase Access to Care, (ii) decrease the cost of care and (iii) improve outcomes. These three macro-needs deserve clarification so they are well understood by companies and investors who have an interest in bringing their technology or products into the U.S.

(i) Increase the access to care:

The goal of Increasing Access to Care is to enable the U.S. care delivery industry to serve more patients. This can be achieved with technologies that augment the capacity to handle more patients by optimizing workflows and reducing defects. The transformation of the current Pathology workflows using digital pathology imaging and digital exchange workflows is a good example, currently in full expansion[ii].

But Access also means Proximity and Affordability. These two dimensions are easy to understand from the patient’s perspective. The Proximity criteria relates to the time it takes to reach the relevant care-giver. The Dartmouth Atlas of Healthcare[iii] generates visual maps showing the amount of hospitals available to patients within comparable driving distances. This helps understand the variability between U.S. regions.

Affordability relates to the patient’s capability to purchase healthcare services. Affordability is extremely variable across the U.S., depending on the patient employment status, age, and insurance coverage, just to mention a few. Affordability of healthcare services is at the nexus of the Affordable Care Act[iv] passed by Congress and signed into law by President Obama in March 2010.

(ii) Decrease the cost of care

The growing burden of healthcare costs has been discussed above and the cost reduction benefit of a new MedTech product/solution is of the upmost importance. Not only do cost/benefit rationales need to be established to support the introduction of new technologies, but they must be substantiated in a significant way that will convince any disciplined healthcare accountant or CFO to bring them into their system -for instance, savings need to directly “connect” with the Profit and Loss statement of the Healthcare institution.. These cost benefits must have a short term (less than 1 year) economic impact to appeal to most commercial insurance companies.

As a result MedTech entrepreneurs must develop a comprehensive, detailed and documented understanding on how their new product / technology impacts the cost structure and the balance sheet of a hospital, surgical room, nursing center or retirement home – just to name a few. They also must understand how their value proposition fits into the business model of such institutions, which can significantly vary from a traditional non-profit hospital to one of the newly created Accountable Care Organizations[v].

In the same way clinical outcomes are measured in clinical trials, economic outcomes must be proven in “real life” and in the relevant U.S. operational context.

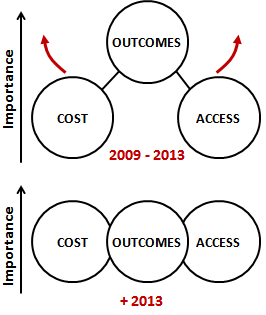

Figure 1. In relatively short years, the dominants claims and attributes of the medical technologies that are in demand have moved from mainly clinical outcomes to a balanced set of cost, access and care delivery outcomes (including all aspects of patient care).

In a 2013 paper published in the MIT Technology Review[vi], Jonathan Skinner writes on the “costly Paradox of Health-care technologies”, pointing out that healthcare is one of the rare industries where technology increases costs. Quoting that only 0.5% of medical studies actually look at cost saving technologies, he challenges the MedTech community to rethink the way it looks at technology R&D for healthcare.

One of the emerging best practices – and one of our recommendations - is to include relevant economic measures as secondary outcomes in every clinical trial, or to amend on-going trials (most of which have been designed and launched with primary clinical outcomes only). The robust analysis of clinical and economic outcomes will position the product for a solid launch and commercialization. The selection of these economic outcomes is intimately linked to the target segment(s) where the product will be offered, and must include effects/improvements that can be seen either upstream or downstream in the care delivery workflow that is impacted by the product.

(iii) Improve patient outcomes

In the context of evolving healthcare in the U.S., and in particular in the area of medical technologies “improving patient outcomes” must be looked at broadly, as opposed to the traditional “solving an unmet medical need” only.

Improving patient outcomes is related to the overall distribution of the quality measures of the care delivery process, including its variance and its defects.

In other words, reducing the variance of clinical outcomes across the U.S. landscape and eliminating defects of care delivery should be considered as “medical needs”, and added to the objectives of improving outcomes for any innovative MedTech company.

Perhaps some facts can help underscore the magnitude and urgency of the opportunity:

· Rates of coronary stents are three times higher in Elyria, Ohio, compared with nearby Cleveland, home of the prestigious Cleveland Clinic[vii].

· U.S. and UK data show that much of the variation in clinical protocols is accounted for by the willingness and ability of doctors to offer treatment rather than differences in illness or patient preference. Identifying and reducing such variation should be a priority for health providers[viii].

An example on how technology impacts outcomes can be found in “The RFID Visual Guide to Healthcare” published by McKesson[ix] where the “outcome” value proposition is stated in the form of “Improving Patient Safety” as “RFID technology protects patients by managing and tracking drug administration and by controlling patient access to unsafe or prohibited areas”.

Another example comes from Leica Biosystem’s laboratory workflow solutions[x] for anatomic pathology. The related value proposition directly addresses the reduction of defects and variance of the workflow: “…solutions that enable remote, real-time viewing and easy distribution of images for collaboration, and Precision image analysis solutions to improve clinical and research productivity, reproducibility, and consistency”.

In short, there are numerous market opportunities in the U.S. for new technologies that enable a more effective care workflow and eliminate its related defects.

About Patient Centricity and Consumerism

Educated readers will probably note that we are not including in this discussion the increasing role of patients in the U.S. Healthcare system. Indeed, this is a significant and growing market force with very specific needs and buying habits. Opportunities such as the “Do-It-Yourself Healthcare” [xi] or the “Retail Healthcare” and the empowerment of the patient in the selection of his/her provider [xii] and its related m-Health constellation of “apps” are significant opportunities. To simplify the discussion in this paper, we decided to exclude them.

Using technology to address the pain points of healthcare

Now back to the technology with more examples to show how technology platforms are enablers of solutions that address current Healthcare pain points. The following examples address at least two of the major paint points discussed above, in a compelling way:

Reducing time in the hospital through improved surgical outcomes enabled by battery-powered tools that use ultrasonic, radiofrequency, laser or light to execute minimally invasive surgical procedures and improve infection control.

Improving and expediting diagnosis with technology platforms enhancing “in-situ” and “virtual” pathology, eliminating heavy and manual workflows in the “gross-room”.

Enabling remote patient monitoring with the emergence of connected health technologies coupled to cloud-based interfaces, storage, data processing and soon care delivery assisting technologies, particularly relevant in the area or chronic conditions.

Synchronizing the care between the hospital and the home, where technology enables and streamlines care delivery workflow migration from the hospital (the place for acute care) and the home (the place for robotic rehabilitation and remote disease management…), including the digital management and optimization of “field-based nursing teams”.

Some of these examples are quoted from the MIT Technology Review Online paper of Dr. Robin Lee and Dr. Gillian Davies which illustrates and discusses them in further detail[xiii].

Building evidence

Prospective clinical trials or sometimes retrospective trials continue to be the preferred method to build evidence to support a clinical outcome claim. Even though trials can be faster and less capital consuming for medical technologies than for drugs, they consume two to five years in the planning, execution and final communication. This interval of time is very comparable to the time it has taken for the U.S. market to prioritize cost and access attributes at the same level (if not higher) than outcomes (Figure 1). As a result, many medical technologies are now reaching the market with evidence that covers “only” clinical outcomes, and lack evidence on their “cost/workflow” and “access” impact. Unless secondary outcomes related to cost, access and care delivery workflows were added during the trial as astute amendments, these products come to market with a competitive weakness.

Building evidence for cost, outcomes and access requires an urgent evolution in all MedTech companies, and this is an acute situation for the companies that are located outside the U.S. and do not benefit from the local ecosystem effect.

It also requires a greater “intimacy” with their end users, not only their clinical users, but all the stakeholder and workflow participants who are affected by their technology, which should result in potential staffing adjustments (for instance to increase the perspective of hospital workflows in the design and configuration of a product).

Designing for the U.S. Market

In the paragraphs above, we have summarized the current pain points of the U.S. Healthcare Markets and suggested how clinical trials and possibly venture teams need to be redesigned to appropriately prepare and execute the development of new technologies prior to their U.S. Market introductions.

Companies that are in planning phases for a new product introduction (start-ups or companies working on their product portfolio) with a projected U.S. launch must consider the new pain points of the U.S. market as they design their new product concepts, or reach the first milestones of their product development cycles.

Simply said: if your product concept does not address outcomes, cost, and access attributes, and if such attributes cannot be proven with a well designed clinical trial (or “economic trial”), then pause, reassess your team and customer knowledge, and start again.

Read Part 2: “ Designing for FDA”

References:

[i] Health Care Costs 1o1” by Katherine B. Wilson at the California Healthcare Foundation (web link)

[ii] “Digital Pathology”, Wikipedia Webpage (web link)

[iii] The Dartmouth Atlas of Healthcare: For more than 20 years, the Dartmouth Atlas Project has documented glaring variations in how medical resources are distributed and used in the United States. (web link)

[iv] The White House - Health Reform (web link)

[v] Accountable Care Organizations (ACO) overview on the CMS website ( web link)

[vi] “A Cure for Health-Care Costs”, MIT Technology Review, Nov/Dec 2013 (web link )

[vii] The Dartmouth Atlas of Healthcare, Reflections on Variations (web link )

[viii] Time to tackle unwarranted variations in practice”, J.E.Wennberg, BMJ 2011; 342; d1513. (web link)

[ix] RFID Visual Guide to Healthcare” , McKesson

[x] Leica Biosystems “ePathology” webpage (web link)

[xi] Joshua Riff, Medical Director of Target, discusses how technology is enabling the DIY Patient. Featured on the PricewaterhouseCoopers Healthcare Web pages (web link)

[xii] “Take Control of Your Health”. Microsoft HealthVault teaser statement, Home Page of the web portal (web link)

[xiii] “Technology: the Cure for Rising Healthcare Costs ?” View from the Marketplace. R.Robin and G. Davies. MIT Technology Review, September 2013. (web link )

[1] Mathieu M. Petitjean, Ph.D. is the CEO of MedNest, based in Princeton, NJ, USA

[2] Susan Z. Paquette, MBA is an Executive Consultant at MedNest, based in Minneapolis, MN, USA

MedNest is a contract Operations Company specialized in the US market entry of Medical technologies based in Princeton, Boston and Minneapolis in the USA. MedNest has launched +45 products and ventures since 2007, in particular in the area of convergent medical technologies.